Thursday, Nov 18, 2021

Professor Daniel Druckenbrod will expand his study of tree rings to Asia, Australia and New Zealand

by Adam Grybowski

Professor Daniel Druckenbrod has been awarded a $93,133 grant from the National Science Foundation as part of a multi-university project that will generate data about how the climate has changed over time in southeast Asia, from the Himalaya to the Southern Ocean, over the past 500 to 1,000 years.

The project will build on and expand Druckenbrod’s ongoing research of measuring tree rings, which indicate a tree’s growth rate over time, to make inferences about past events.

“The value of studying tree rings for this project is that they can help augment our understanding of past climate in this part of the world,” says Druckenbrod, who is chair of Rider’s Geological, Environmental & Marine Sciences Department. “That information becomes especially timely as we think about climate change.”

Analyzing tree rings, which is known scientifically as dendrochronology, assigns a specific calendar year to each ring using a common climate signal shared across trees in a region. To those who know how to read them, tree rings also function more broadly as a kind of weather history reference book. They can, for example, show whether a tree suffered freeze damage at some point in time or lived through drought or wet seasons.

There is a great opportunity here to make a difference

The new grant funding will deepen an ongoing collaboration with scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the University of St. Andrews and will develop new connections with scientists in Australia and New Zealand.

Because of his international collaborators, this project will not involve much field work directly for Druckenbrod. But it will provide the opportunity, he says, to apply new approaches and scientific methods while gleaning information from existing samples and collections.

“Tree rings have been traditionally assessed by measuring their width, which leads to a lot of insight about the past environment,” Druckenbrod says. “We’re now looking at how they absorb and reflect light — a different way of accessing or quantifying a climate signal.”

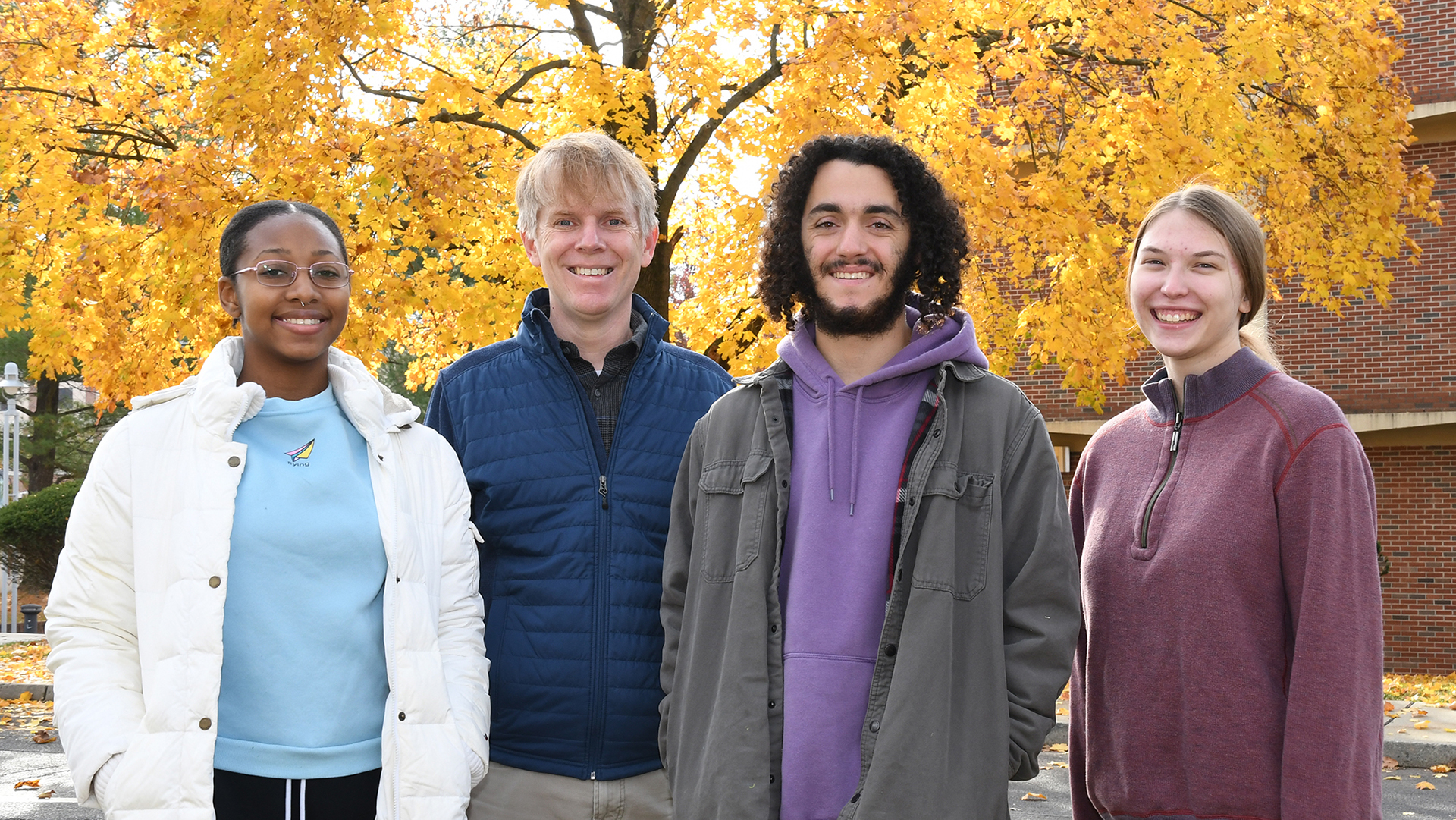

Three Rider students will assist Druckenbrod with primary data analysis as he pushes ahead into new territory: Robby Arpaio, a junior majoring in marine sciences, Stessie Chounoune, a junior majoring in environmental sciences, and Gabby Banyacski, a sophomore majoring in environmental sciences.

The scope of the three-year project will give these students the opportunity to conduct research over an extended period of time in collaboration with premier research institutions like Columbia. Their involvement may also include working on publications and conference presentations.

“I’m still not exactly sure what I want from a career, but I definitely know I have an interest in the environment," says Banyacski, who is also a member of Rider's Green Team, a group of student volunteers working to improve campus sustainability. "I’m really excited to be able to experience what research can be and see if it's something I want to continue pursuing. It's possible I'll be able to experience this project from start to finish."

Druckenbrod has been collaborating with other scientists since he began studying the environment at the University of Virginia, where he earned a doctorate in 2003. He has worked closely with partners on major historical sites in the Eastern United States, including Monticello and Mount Vernon, which were the agricultural plantations of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, respectively.

The importance of scientific collaboration, Druckenbrod says, continues to grow. “The problems we need to tackle are so complex and involve so many disciplines, they are best answered with a team of scientists. At Rider, collaboration is also a great way to generate connections for students.”

The imperative to act in solving climate change has been evident to Druckenbrod since he was a graduate student. “There's always been an urgency, but it has increased over the past couple of decades,” he says. “It has come to the point where the effects of climate change are more evident and more pronounced than ever. Personally, it makes me motivated as both a researcher and a teacher to not only contribute to the science but also to help people understand how the world is changing. There is a great opportunity here to make a difference.”