by Adam Grybowski

PILLARS OF THE COMMUNITY

Sometime in the late spring or early summer of 1792, a man named Samuel Hunt Sr. and his nephew Elias sat in jail after pleading guilty to manslaughter.

Samuel and Elias were descendants of one of the founding families of New Jersey’s Maidenhead Township, the forerunner to what is called Lawrence Township today. Samuel and his wife, Sarah, had five children and also owned two enslaved boys, Peter and Charles, and a 16-year-old enslaved girl named Hagar.

According to testimony in the manslaughter case, on the morning of June 4, the Hunts tied Hagar to “a plum tree near the house.” Elias claimed that Hagar had been caught in a scheme to poison the Hunts. As punishment, Elias and Samuel whipped the young woman with “six or seven thick hickory sticks,” according to a witness. The thrashing produced a confession of guilt under extreme duress, and Hagar also professed where the poison could be found. (No poison was ever located.)

It’s not clear how long the whipping lasted, but by nightfall, Hagar was dead.

An inquest ensued, and without dissent, witnesses concluded that Hagar’s death was the result of a brutal whipping. An autopsy determined the cause of death as blood in the lungs, which the doctors attributed to Hagar’s manic screaming during the beating. Samuel and Elias were indicted, and a 24-person jury then ruled that the severe whipping killed Hagar. Samuel's wife was accused of being an accessory to the crime.

After serving at most two months, Samuel and Elias were both released from jail in early August. Samuel’s £300 bail was paid by two pillars of the community, a man named Joseph Brearley, whose distinguished family included a signer of the U.S. Constitution, and a Revolutionary War veteran, statesman and fellow slaveholder named Benjamin Van Cleve.

A FAMILIAR NAME

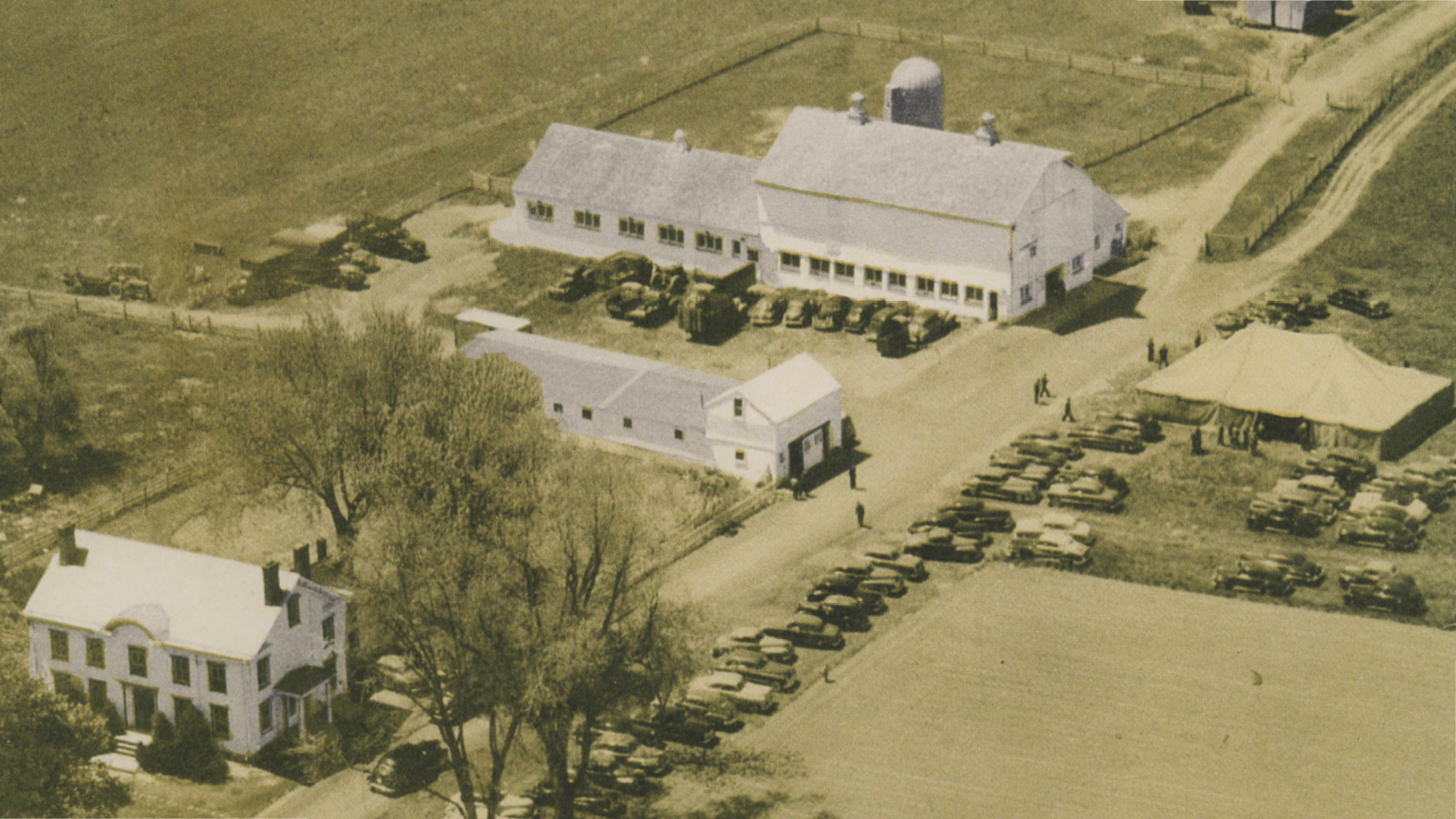

The name “Van Cleve” is probably familiar to many people who are or have been associated with Rider. A house bearing the name was part of the 140-acre farm that Rider purchased in 1956 as it planned to move its campus from Trenton to Lawrenceville. The house has been part of the University’s campus ever since, first as a student residence, then as the Admissions building and, since 1993, as the location for Rider’s Office of Alumni Relations.

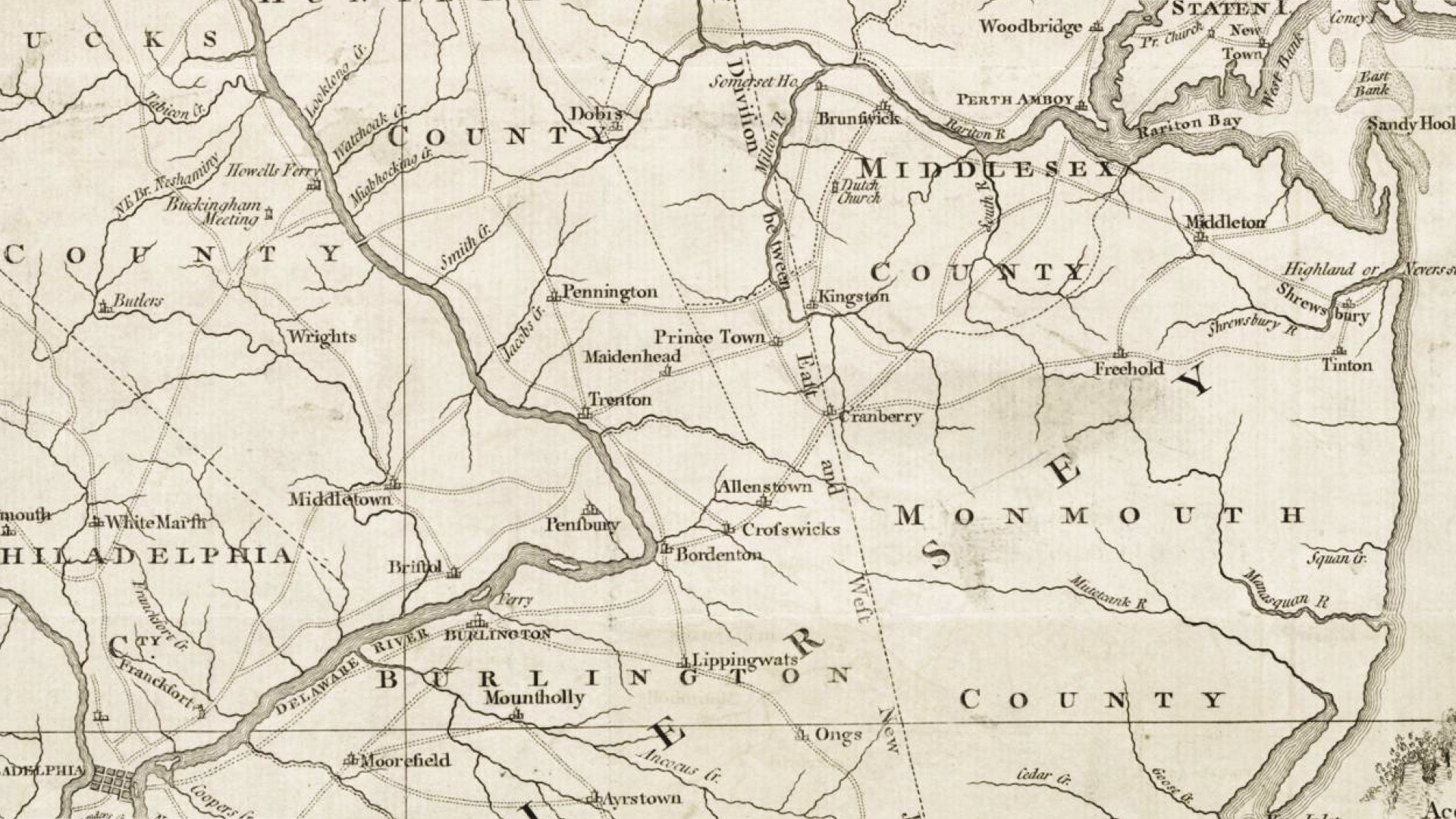

Born in Maidenhead in 1739, Van Cleve originally purchased the property on which the house was subsequently built in the early 1770s. During the Revolutionary War, he served as captain and major in the First Hunterdon militia. Less than two months after the U.S. declared independence, he fought in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776.

His military service ended on Nov. 13, 1777, following his election to the New Jersey Assembly — a body he served in almost continually until 1802, including four times as speaker. His political career also included serving as a justice of the peace, a judge on the Court of Common Pleas for Hunterdon County and the head of Maidenhead’s government.

While in one sense he was devoted to liberty and justice, the fullness of Van Cleve's life story has remained obscure until only recently. In July 2020, Rider formed a task force charged with proactively researching the institution's historical relationship and connection with slavery and enslaved people. Dr. Brooke Hunter, an associate dean of Rider’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, where she is also an associate professor of history, and Dr. Evelyn McDowell, the chair of Rider’s accounting department, co-chaired the task force. Its work, so far, has centered on the only known connection between the University and slavery: Benjamin Van Cleve.

Although his stature is minuscule compared to the Founding Fathers, like them, Van Cleve embodies the inherent contradiction of the American experiment: He simultaneously fought for the ideal of liberty while participating in and championing the cruelty of chattel slavery and the degradation and dehumanization of Black Americans.

“The story of Benjamin Van Cleve forces us to confront the paradox of liberty and slavery in American history,” Hunter says.

Uncovering the Van Cleve story has placed the University into the national conversation about who we as a country choose to honor and memorialize, especially as it relates to slavery, the ongoing effects of systemic racism and the contentious quest for racial justice. But Van Cleve’s story also serves to illuminate the often-misunderstood history of slavery in northern states like New Jersey.

“The violence of slavery was certainly not confined to the South,” Hunter says.

LIFE ON THE FARM

On Dec. 31, 1778, the New Jersey Gazette ran an advertisement announcing a reward for an enslaved woman named Dinah who had run away from Van Cleve on the day after Christmas. Van Cleve had purchased her only recently from a clergyman in Springfield, N.J.

Van Cleve was willing to offer a reward for what he considered substantial "property." The advertisement suggested Dinah may have been seeking out her brother in Freehold, N.J. Her fate, whether she was returned to bondage or not, remains unknown.

Because of a lack of historical sources, we don't know exactly what the experience of enslaved people like Dinah was like in Maidenhead. But if it resembled other rural areas in New Jersey, Hunter, who is also the current Lawrence Township historian, says it would have been on a much smaller scale than Southern plantations. In general, slavery in the North did not play the same central role in the economy as it did in the South.

By 1799, Van Cleve owned about 254 acres, making him the seventh largest landowner in the township. (His brother Aaron, who was also a slave owner, was ahead of him at number six, owning about 275 acres of land.) At the time, Van Cleve’s house was surrounded by fields that grew wheat, rye, oats and corn. The crops were destined for markets in Philadelphia and New York, though some may have been exported to Europe and the Caribbean, where they would have been used to feed enslaved people working on sugar plantations.

Hunter says slave quarters did not exist in the township, meaning Van Cleve and the men and women he enslaved lived together in his house. Enslaved men worked alongside their masters, and also perhaps white indentured servants, as agricultural laborers. Enslaved women, like Dinah, primarily worked at domestic tasks like cooking and cleaning.

Despite the smaller scale of slavery in places like Maidenhead compared to Southern plantations, enslaved people suffered equally in the North and South, says Hunter. “Slavery in the North was just as dehumanizing as in the South. There are clear cases of brutality in the North, including in New Jersey and Lawrence Township. Evidence documents conflict and physical violence between masters and enslaved people and reveals the oppressive and dehumanizing character of slavery.”

NEW JERSEY'S GRADUAL ABOLITION

Slavery was introduced into New Jersey and the surrounding region by the Dutch in the early 1600s. It expanded after the English gained control of the colony in 1664. It took until the approach of the Civil War for New Jersey to seek a decisive end to the practice. It was the last state in the North to abolish slavery.

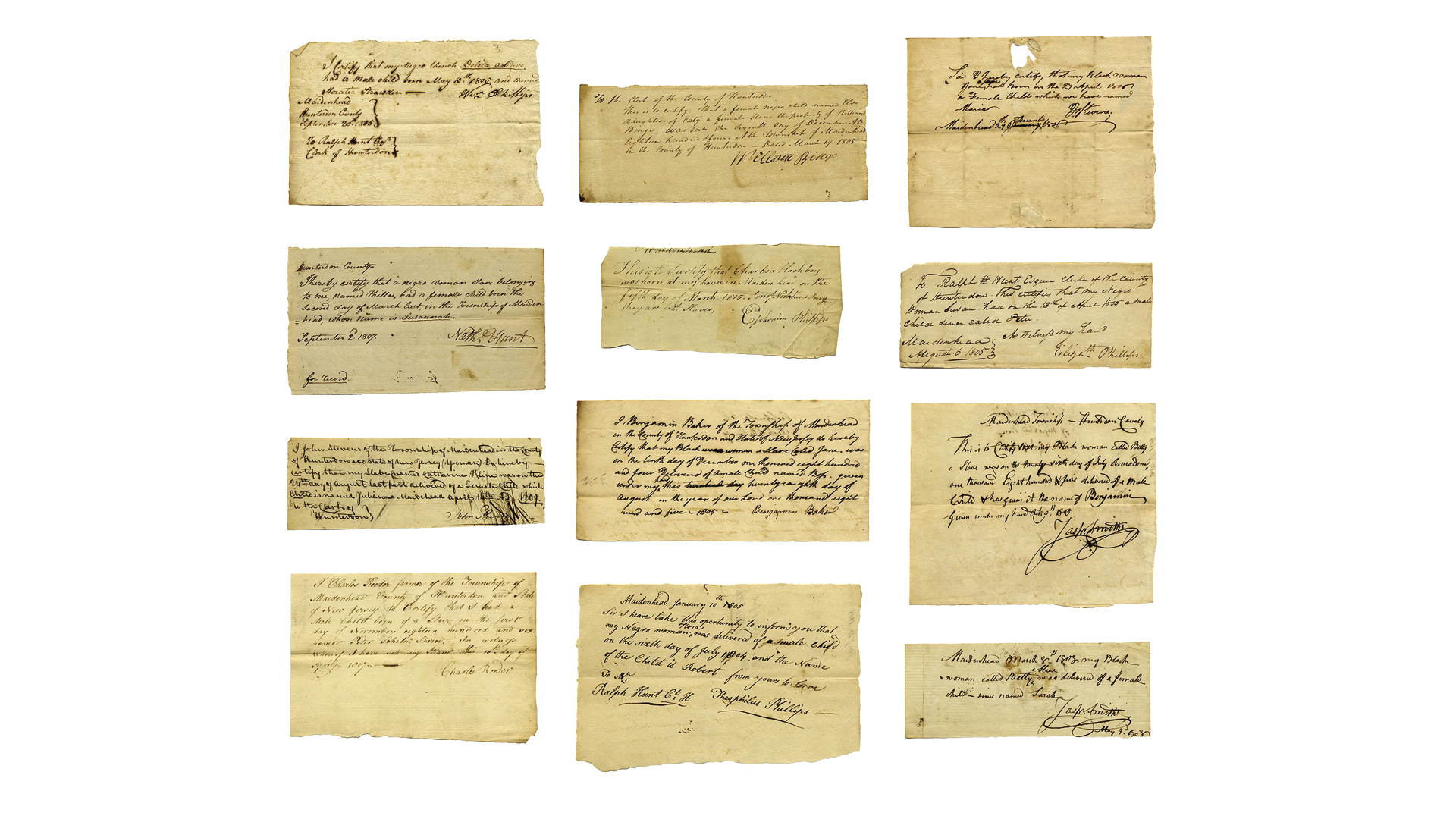

For the New Jerseyans who favored abolition, their approach to ending slavery reflected a contradictory state of mind: They disagreed with the institution of slavery yet did not want to voluntarily free their slaves. As such, the state legislature passed “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” in 1804. According to the law, females born of enslaved parents after July 4, 1804, would be free upon reaching 21 years of age, and males upon reaching 25.

“In effect, the 1804 Act created slaves for life and term-slaves, but their daily lives were indistinguishable,” Hunter says. “New Jersey’s law was anti-slavery but also pro-slaveholder.”

Van Cleve did not vote on this act because he had lost his bid for re-election in the New Jersey Assembly the previous year. However, he either argued against or opposed gradual abolition while representing his county on several occasions. In 1798, Van Cleve voted in favor of maintaining slavery as a racial system of perpetual bondage, passed from mother to child, and for strengthening restrictions on enslaved peoples.

In 1846, “An Act to Abolish Slavery” reclassified the status of enslaved people as apprentices for life. Far from achieving emancipation, the act, in essence, gave slavery a different name. These apprentices continued to be listed more accurately as “slaves” on the 1850 and 1860 federal censuses.

Slavery persisted in New Jersey up to and through the Civil War until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. In Lawrence, the last known living enslaved person was recorded in 1860 — Sylvia Hunt, age 95.

For Van Cleve, it appears he lived with individuals who were not free up until the day of his death, Aug. 31, 1817. Court records from earlier that month show his residence included a nameless woman and boy, both Black, and a “bound” 16-year-old named Abigail Coulter. It's possible all three were either enslaved or, at a minimum, indentured servants.

OUT OF THE SHADOWS

The Van Cleve house passed out of the family’s hands in 1824. Since then, it has withstood significant changes over time.

Its current form — a distinctive Italianate style — would probably be unrecognizable to its original builder. In fact, an inspection in the 1970s by the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry concluded there was little evidence of it being an 18th-century house at all. The report surmised the current house was in essence built around the original building — a project likely undertaken by one-time owner Benjamin White sometime before Rider purchased it.

Recently, more changes to the house have been proposed. The task force has prepared and submitted a report of its findings to President Gregory G. Dell'Omo, Ph.D., and presented to the Board of Trustees. The report includes a set of recommendations on how Rider can recognize this history and increase educational opportunities around it.

These efforts would include acknowledging Van Cleve’s story and the story of slavery in Lawrence Township, as well as adopting historical markers in and around the house that memorialize

the enslaved people who suffered from the brutalizing institution of slavery on the surrounding land. Also among the proposed actions is removing the name “Van Cleve” from the building.

“These actions would represent a clear sign of respect for our University community, especially the students, faculty, staff, alumni and donors who are descendants of enslaved people,” says McDowell, who in addition to co-chairing the task force is also a founding board member of the National Society of the Sons & Daughters of the United States Middle Passage, a lineage society that works to preserve the memory and history of slavery.

Both the Board and President Dell'Omo have expressed support and gratitude for the task force's work, and the Board is set to vote on a resolution to accept the recommendations of the task force in October.

The task force’s recommendations would elevate some of the people who have traditionally been subsumed in the shadows cast by those who held power over them, including the power of life and death. At Rider, this would include people like the enslaved woman Dinah, who courageously sought her freedom at great potential peril.

“For centuries, names like Van Cleve have been held up as exemplary while the people who suffered at their hands have remained nameless and unknown,” McDowell says. “Hopefully, our actions could help to right this injustice and help create a truer portrait of our history, especially locally. We still have a lot to learn about the American story — and a lot to gain from that knowledge.”