by Adam Grybowski

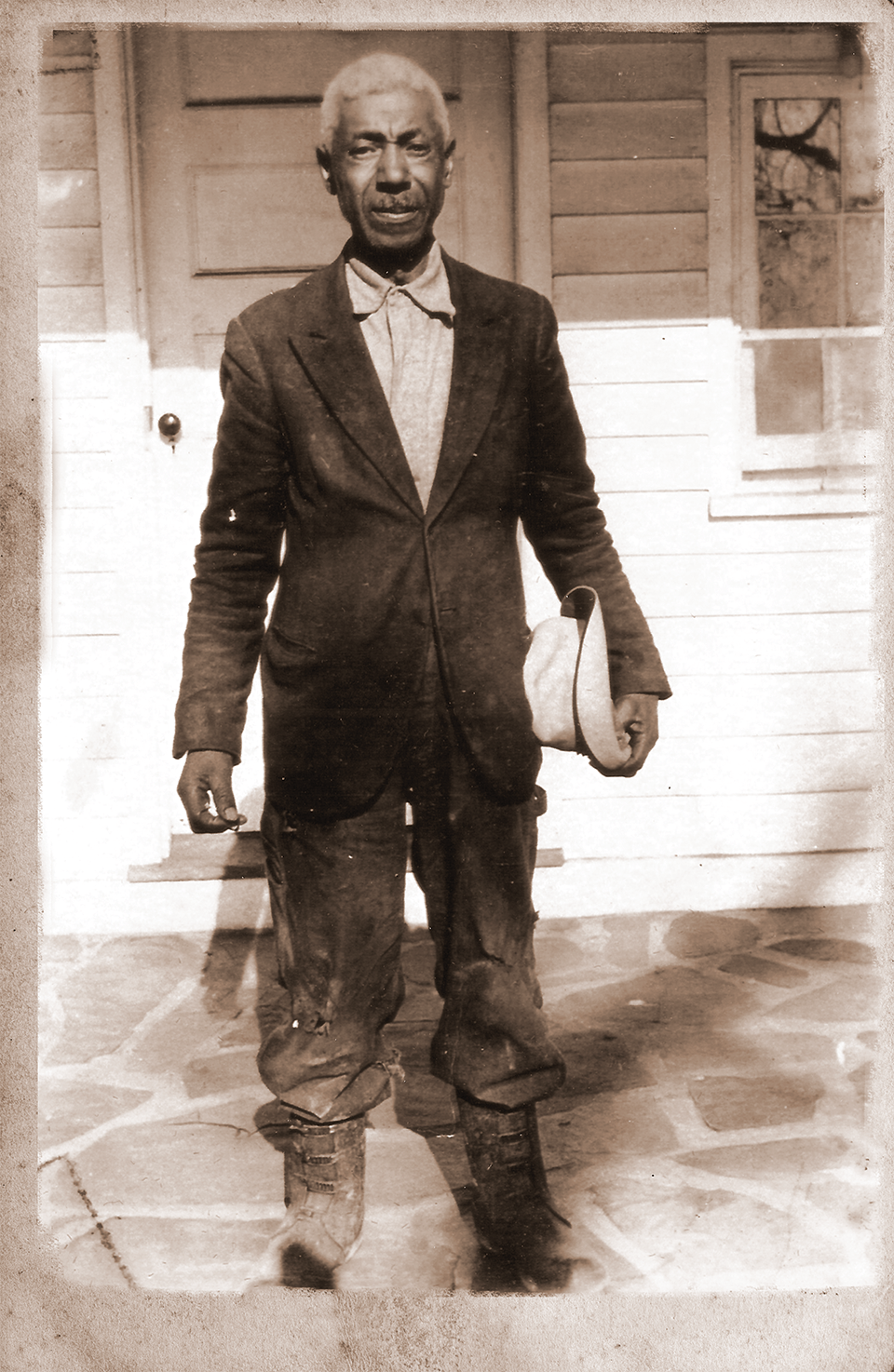

After a startling entrance into business and an equally unusual exit, Herbert Hubbard worked for most of his life on a 70-acre dairy and vegetable farm run by a white family named Pembleton.

Despite working as a sharecropper, Hubbard, who was black, had an education that prepared him for white-collar work. In 1894, he graduated from Trenton Business College, a forerunner to Rider University, making him the University’s first confirmed African American graduate. Upon graduating, he would find employment that conflicted with the mores of post-Civil War America, cutting his promising professional life short.

The naming of Hubbard as Rider’s first confirmed African American graduate came this fall after the University’s archivist, Robert Congleton, and Hubbard’s great-granddaughter Beverly Mills met to discuss the issue. Hubbard’s status was a family legend for generations.

“Over the years, I’ve been asked time and time again: Who was the first African American to graduate from Rider?” Congleton says. “Now, I have an answer.”

It is possible that prior to Hubbard, Rider may have graduated African Americans who passed as white students unbeknownst to school officials, Congleton says.

Hubbard’s name appears in the annual bulletin published by Trenton Business College to advertise courses and requirements, share tuition costs, and list current students and recent graduates. A brilliant penman and skilled musician, Hubbard is listed as an 1894 graduate, but because the publication did not include photos, it was impossible to distinguish the race of students without further details.

Born June 7, 1875, Hubbard was the only child of a woman named Kate who worked as a housekeeper for a wealthy Hopewell, N.J., family, the Stouts. Kate, who was a single mother, died when Hubbard was a boy, though it remains unclear his exact age at the time of her death.

After Kate died, J. Hervey Stout and his sister, Sarah, raised Hubbard. Both single, they lived together in a house on what is now Broad Street. The siblings were distinguished for maintaining “one of the most hospitable homes in the Hopewell valley,” according to a book of early Hopewell history, Pioneers of Hopewell.

“I don’t know if they did it because of a sense of loyalty to Kate, who had been there a long time, or if they saw something worth investing in,” says great-granddaughter Mills. “Maybe it was both.”

According to family stories, Hubbard was a self-taught musician who not only played the violin but made the instrument too. He passed his musical gifts on to his son William Earl, who was a well-known local musician for some 50 years. Hubbard’s musicianship was second only to his penmanship. “Apparently, his penmanship was absolutely extraordinary, and he would drill his children, impressing upon them the importance of good penmanship,” Mills says.

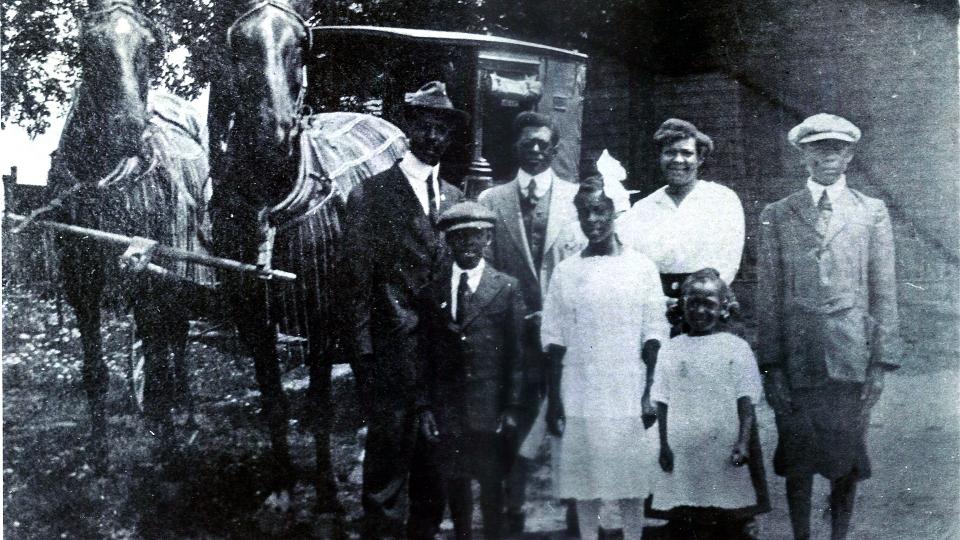

Mills and Congleton believe the presence of a wealthy patron was instrumental in Rider admitting Hubbard. “Someone would have had to not only advocate for him, but pay for him,” Mills says. “The Stouts must have seen something special in him.” If this is true, Hervey is the likely candidate. He appeared at several significant events in Hubbard’s life, Mills says. When Hubbard married Sarah Matilda Hoagland in 1897, Hervey served as a witness. Hubbard named his first son, who died at a young age, Hervey. “Hervey obviously cared about Herb,” Mill says. “If he didn’t, he wouldn’t have done these things.”

Before the Civil War, opportunities for free blacks to pursue higher education were limited in the North and virtually nonexistent in the slave holding South. In response, many historically black colleges were founded with the primary mission to educate African Americans. More opportunities arose for blacks following the Civil War, when private colleges enrolled more African Americans than did public institutions, often preparing them for professional jobs.

Booker T. Washington, the president of the Tuskegee Institute, led the shift toward educating blacks, with the goal of securing them jobs in manual labor, where more jobs existed. For instance, in the 1890s, while Hubbard was studying at Rider, New Jersey opened a Manual Training & Industrial School for Colored Youth (known as the “Tuskegee of the North”) in Bordentown. “This segregated residential high school provided vocational training for African American men and women in manual labor jobs,” says history professor Brooke Hunter.

At Trenton Business College, Hubbard likely studied the standard curriculum of penmanship, shorthand, stenography, public speaking and other subjects related to business. Bucking the trend led by Washington toward manual labor, Hubbard used his gifts to transcend contemporary expectations for African Americans — a feat he accomplished, but only for a limited time. According to Mills, Hubbard told his children that he worked for three years after graduating, saying that he was employed in the back room of two offices (most likely a bank and an insurance company) to keep out of sight of white clients who may have been offended by seeing a black man in such a position. “He would be the one penning specific documents, but the business owners couldn’t ever show that a black man was writing them,” Mills says.

Hubbard and his wife would have three children after the death of Hervey: William Earl, Herma (a combination of his first name, Herbert, and his wife’s middle name, Matilda) and Florence Leona. In 1898, a year after he was married, Hubbard was no longer employed in business but instead, at the age of 23, became a sharecropper for a local family. The exact nature of this transition is unknown. “The only thing I can think of is that farming was a sure shot, and he had to provide for his family,” Mills says. “It couldn’t have been easy for him.”

Hubbard began working on the farm in 1898 and lived in a section of the Pembleton house with two bedrooms upstairs and one large room downstairs. The Pembletons had indoor plumbing and running water, but Hubbard didn’t. He got water from a well and used an outhouse behind the home.

Despite lacking modern amenities, the farm provided a living. “I remember the pantry on the farm as being like a wonderland,” says Hubbard’s grandson, Stanley Stewart II, who was born in 1937. “There were jars of just about everything that could be grown and canned, along with smoked hams and sausages and such.”

The farm sold its milk to nearby Borden Dairy. Stewart explains that cows were milked twice a day, seven days a week — first at 4 a.m. and then again at 4 p.m. When not completing the work himself, Hubbard received help from his son and son-in-law. Hubbard worked on the farm until around 1947, when the Pembletons sold it. The sale left Hubbard “virtually homeless,” Stewart says, and, as a result, he moved to 233 S. Main St. in Pennington to live with his oldest daughter, Herma. Hubbard died in Pennington on July 11, 1948, from stomach cancer. He was 73.

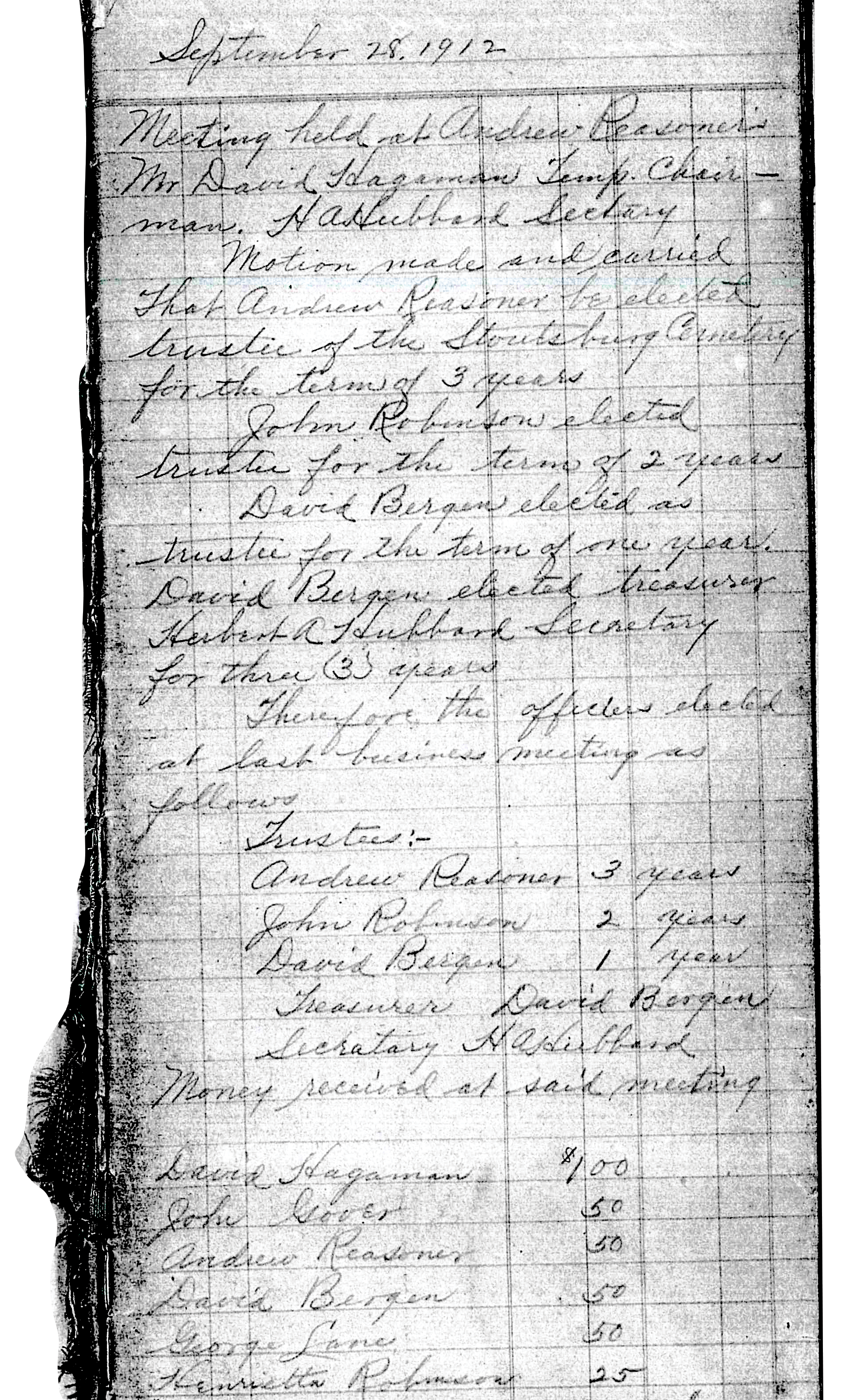

Hubbard was buried in Stoutsburg Cemetery, where Mills currently works as secretary on the cemetery’s trustee board. She has been conducting research for a book about the contribution of African Americans to the Hopewell region, and her great-grandfather’s story is one she hopes to tell. “He’s just one person out of many who has a fascinating story,” she says. “So many of them were extremely talented people and the economic engine of the region. If they were born today, who knows what they would have accomplished.”