by Aimee LaBrie

Krishna Powell ’05 was tired. At 25, she had a young daughter and a full-time job that required much of her focus. Her paycheck was little more than minimum wage, so she relied on government assistance to feed her child. She had taken a few classes at Mercer County Community College and also started at Rider University for a semester, but when it came down to paying rent or paying tuition, she had to be practical. She knew that it would be difficult (if not impossible) to get ahead, but there seemed to be nothing else to do.

All of that changed when she spoke with an advisor at Rider who mentioned the Charlotte W. Newcombe Foundation, which was created specifically to aid women over 25 with challenges similar to Powell’s. Seeing her chance, Powell applied for and was granted Newcombe Scholarship funds from Rider to begin taking classes again. Powell could not believe it. “I was this little girl from Trenton whose mom struggled to make ends meet,” she says. “The scholarship was life-changing for me and for my family.”

Her three daughters, particularly her oldest, Brenaea Fairchild, watched her struggle, one class at a time. “She saw my drive to return to school and do what needed to be done,” Powell says. “She was at the foot of my bed when I was studying late into the night.”

At one point, Powell again stopped taking classes. She was in the process of getting a divorce, raising two children alone and working full time. “I thought, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I only had one more class to take, but it seemed out of reach.”

She was away from Rider for three years when a woman from the College of Continuing Studies called and said, “Krishna, your folder has come across my desk, and you are one class shy of graduating. What’s going on?”

“I explained my situation and said that I had too much going on,” Powell says. “I started crying, and she kept talking to me. She called me again the next day, and she said, ‘You can do this. You’ve got one class to go. Come on, Krishna, you can push through this.’”

And, with the support of her family, she did. “My mother watched my girls at night so I could take classes at Rider.”

It may have taken Krishna a total of six years to graduate from the moment she first set foot in a Rider classroom to receiving her diploma, but she finally earned her bachelor’s degree in liberal studies along with a certificate in public relations in 2005. Professionally, she began to move up the corporate ladder. Having started as a receptionist, she is now an executive at Molina Healthcare and has also launched her own human resources consulting firm called HR 4 Your Small Biz.

“Knowing that someone else was willing to invest in me helped me see that I mattered,” Powell says. “When someone believes in you, there’s nothing you can’t do.”

Rider is one of only 42 institutions of higher education that currently receives contributions from the Newcombe Foundation, which provides a dollar for dollar match. For example, if Rider secures a gift of $2,000 toward an endowed scholarship for female students over age 25, the Foundation, in turn, provides another $2,000, doubling the amount and the impact of the gift. The relationship between Rider and the Newcombe Foundation has thrived for more than 30 years, with the Newcombe Foundation contributing $1,423,500 to Rider for student scholarships. One of the five current trustees who guide the foundation is Rider President Emeritus J. Barton Luedeke.

“The Newcombe Foundation has helped literally thousands of women,” says Denise Pinney, Rider’s director of corporate and foundation relations. “It’s an amazing organization that shares our interest in seeing students succeed.”

Rider University students are not the only ones impacted by the Newcombe Foundation. Thomas Wilfrid, Ph.D., executive director of the foundation, which is located in Princeton, manages the scholarship funds that are distributed to dozens of universities across the country. After working in various high-level positions at Mercer County Community College for 38 years (including acting president, vice president for academic affairs and professor of physics), he feels fortunate to have found this role at this stage of his career.

“Being able to find effective ways to help others in need is somewhat like solving a difficult physics problem,” he says. “You uncover the challenge, you analyze the situation and you find the best solution. In providing these funds for those who would not otherwise be able to go to college, we can see positive change right away, and, in many cases, multigenerational impact. I can’t think of a better way to spend my time.”

Charlotte Rachel Wilson was born in Philadelphia on March 28, 1890 — a time when women weren’t expected to go to college. As the youngest daughter of a doctor who believed strongly in philanthropy, she also grew up understanding the importance of helping others. She sold war bonds during World War I, taught women to knit for soldiers and volunteered in the Red Cross. Though she valued education, she was unable to attend college because of serious vision problems that made reading for long periods of time difficult.

She fell in love when she was in her mid-20s. She had been traveling on a steamship with her elderly parents, serving as their companion. At 26, she was already considered by society to be approaching spinsterhood. While on the boat, she met the ship’s first mate, Fred C. Newcombe. Walking together on the deck, they talked and talked and fell in love. By the end of the cruise, Fred asked Charlotte’s father for permission to marry his daughter, but he said no — unequivocally. He could not see his daughter being married to someone who, because of his profession, would spend most of his life away from home. The two parted ways, and Charlotte was certain she would never see him again.

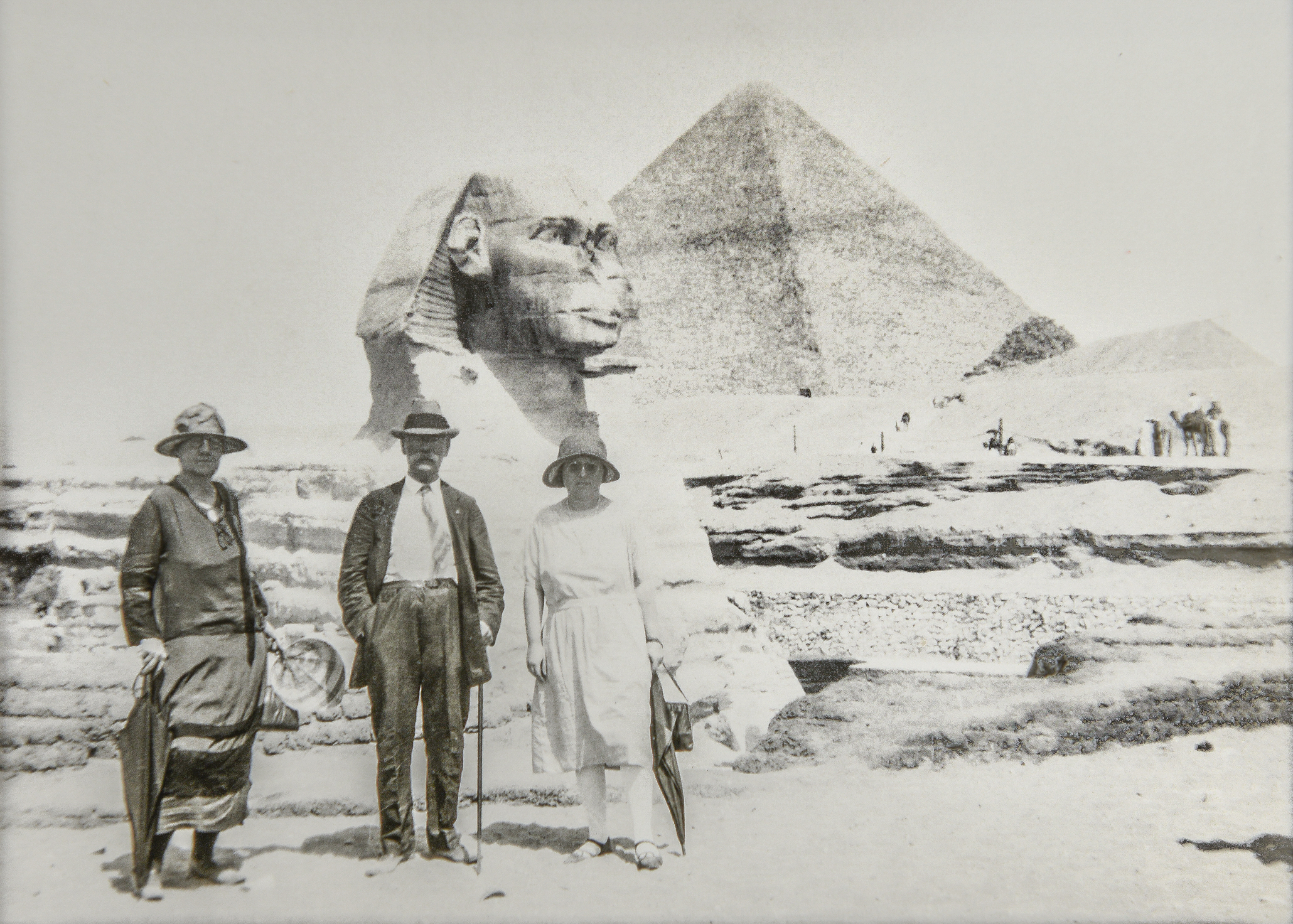

Thirty years passed. Fred married, but after his wife died, he searched for the woman he had met decades before on that steamship. He had never forgotten her, nor she him. Charlotte was 62 when she married Fred, and they traveled for the next decade all around the world, seeing the pyramids in Egypt and the savannas of Africa.

When Charlotte died in 1979, she directed that half of her assets be used to establish a charitable foundation in her name to help students complete degrees in higher education. She left it to the five trustees of that foundation to decide how best to accomplish this goal. The growth in value of the drug company stock she inherited from her father left her with an estate valued at more than $34 million. After consulting with a number of higher education leaders, the trustees agreed to support scholarships for women who were older than the typical college student, many of whom had families and were struggling to make ends meet. In that way, the largest program of the Charlotte W. Newcombe Foundation was born.

“The most important thing for people to know about Rider and the Charlotte Newcombe Foundation is that they don’t give up on people,” Powell says. “They take those of us who society would technically give up on and say, ‘You can do it; I’m here to support you, and I’m going to set you up for success.’ Even if you don’t think you can afford it or if you think you’re too old, they make it possible. As the first person to graduate college in my family, I am living proof.”

Wilfrid, whose wife, Diane, serves as program officer for the foundation, has seen firsthand the impact that scholarships like Powell’s have on hundreds of lives. “In 1981, Rider became one of the first Newcombe-funded institutions, and the very first to offer matching gifts. We have a strong partnership, in part because we both strongly believe funds need to be available to help nontraditional female students succeed, however long it takes them or whatever their life circumstances may be.” Because of his longtime dedication and support of Rider, Wilfrid received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the university in 2010.

And the impact of giving goes beyond the individual. Powell has been able to help support her mother, and she now expects all of her children to go to college, which, at one time, she never would have thought possible.

Powell’s daughter, Brenaea Fairchild, is now a senior at Princeton University on a scholarship, studying history, French and Spanish. “At first, she didn’t think she would get into Princeton,” Powell says, recalling her daughter saying, “I need to be a genius to get in.”

Powell, now married to Tony, has two other daughters, Talitha, age 15, and Toni-Loren, age 7. “I tell my daughters, if I learned nothing else in my life, it’s that you have to at least try. See what happens. Don’t be afraid of the no’s; look for the opportunities.”

To learn more about the Charlotte W. Newcombe Foundation or other opportunities to help students, visit www.rider.edu/give or www.newcombefoundation.org.